Sean Mickalitis

News Editor

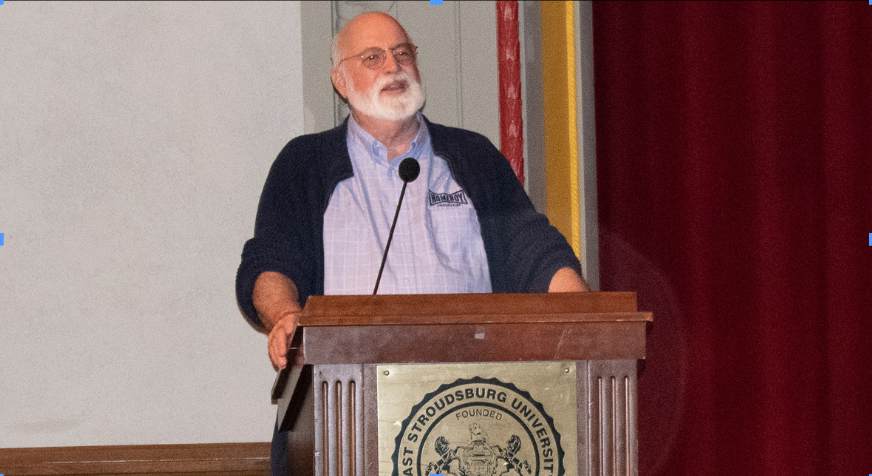

Father Gregory Boyle spoke at the sixth annual Peter Roche de Coppens Sociology and Spirituality Lecture at the Abeloff on Thursday, April 18. Boyle’s presentation was entitled Barking to the Choir: Power and Radical Kinship, where he described his organization and spoke inspiration.

“You imagine a circle of compassion, and then you imagine nobody standing outside that circle. You go from here to dismantle the barriers that exclude,” Boyle said. “You have to go to the margins because that’s the only way [the barriers] will be removed.”

Boyle explained that to remove barriers, one must step outside the boundaries or comfort zone and stand at the margins. He did this when he began Homeboy Industries (HB).

“Every once in a while, you get to stand with the demonized and the disposables so that they will come when we stop throwing people away.”

He thought of something Mother Teresa once said, “the problem with the world is that we’ve forgotten that we belong to each other.”

Boyle then described HB’s status as a not-for-profit organization with a $20 million annual operating budget and 500 employees who provide rehabilitation services for former gang members.

He emphasized that the best way to help a gang member is to not reach for them; it’s being able to be reached by them.

“If you’re going to the margins to make a difference, then how is it not about you? We don’t go to the margins to make a difference. We go to the margins so that the folks at the margins make us different.”

The organization began in Los Angeles, wherein 1988, Boyle was a pastor of the poorest parish in the city, nestled between two housing projects deemed the largest west of the Mississippi River.

Boyle said that 31 years ago, LA County had 120,000 gang members and 1,100 gangs. His church was in a neighborhood with the highest concentration of gang activity.

He said in the 1980s, some schools suspended adolescent gang members. Instead of reading literature and learning of Earth’s ecosystems, the teenagers would sell drugs, engage in violence and vandalize property.

“I asked the kids, ‘If I found a school that would take you, would you go?’ To my surprise, every single one said, ‘Yeah, I would.’”

Boyle contacted local school districts and asked if they would enroll the teenagers, but none would take them.

Across the street from his church was a convent of nuns. He asked them if they would move out so that the gang members could move in, and they agreed.

From then on, it became evident that Boyle was standing out. He was helping the “bad people.”

“People in the parish would ask this question: ‘I thought churches were supposed to be remedially sealed, good people in and bad people out.’ I thought that was a good gospel challenge,” Boyle said.

Now that the gang members had a place to study, many of them said they wished they had jobs. Boyle began looking for felony-friendly employers surrounding the housing projects.

He explained that finding employment for the former gang members was difficult, especially since some members had obscene tattoos such as “F**k the World” adorned on one’s forehead.

Boyle helped his disciples create maintenance and landscaping crews so they could earn money.

In 1992, after the Rodney King verdict, there was unrest throughout LA’s low-income neighborhoods, except for the area surrounding Boyle’s parish. A reporter interviewed Boyle to understand why.

“I told them it’s because we have 60 strategically hired gang members who are working together. They have a reason to get up in the morning, and a reason to not gangbang the night before, and a reason not to torch their community.”

Ray Stark, a movie producer, read the interview in the Los Angeles Times. The article intrigued Stark, who later summoned Boyle to his office.

Boyle recalls Stark saying, “How should I spend my money?” Stark had $500 million and wanted to help the priest’s cause.

Using the funds given by Stark, Boyle and his homeboys were able to start Homeboy Bakery, and a month later, Homeboy Tortillas.

Today, the organization is the largest gang intervention, rehab, and advancement program on the planet. The organization helps 15,000 people a year and 400 men and women through an 18-month program, according to Boyle.

The initiative provides legal assistance, education, anger management and workforce development services.

The father ended his speech with inspiration for all attendees and to reminded everyone that we belong to each other.

“Nobly born, don’t think for a second that ESU is the place you come to, it was always going to be the place you go from, and you go from here to dismantle the barriers that exclude. You go from here to stand at the margins because that is the only way they will be erased.”

Boyle explained that students go from ESU to promote positive change in their communities, in the lives of others, which inevitably changes and reveals the truth hidden within themselves.

After his presentation, Abeloff roared with applause.

“I liked his speech. It wasn’t very emotionally intense, but I liked his message,” said student Tommy Cruznieves.

HB influences over 250 organizations around the world who follow the HB model to help former gang members, according to their website.

Email Sean at:

smickaliti@live.esu.edu