Jazmin Cole

Web Editor

On an early morning before the sun was at its peak families started their daily routines of lighting fires to begin breakfast and dressed to prepare for the day ahead.

“See you tonight!” a young girl said and waved to her family as she walked out to start her day.

At 8:15 a.m. on Aug. 6, 1945 chaos began and that young girl like many, many others left their homes and never came back.

The room was still with silence as hibakusha (what Hiroshima survivors are called) Emiko Okada, recalled horrific memories of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombings on Friday, Feb. 1 in Beers Lecture Hall.

“350,000 people were in the city when the bomb went off,” Okada said.

“I am not here to talk to you about the size of that mushroom cloud but what happened under that cloud,” Okada stated while pacing the front of the room.

The bombings were part of the U.S.’s retaliation methods towards Japan in World War II, nearly 74 years ago.

Now, 81 years old, Okada was only eight years old at the time, but she can still recall some vivid memories of the bombing.

Children who were in third, fourth, fifth and sixth grade were considered too young to help with the war, so they were sent to live with relatives or Buddhist temples to be spared in case their cities were bombed Okada explained.

Unfortunately, after the war when Japan surrendered, and the kids were looking to return home to their families…most of them became orphans.

In the minutes following the bomb was released Okada recalled everything was thrown into absolute mayhem.

“There was a flash and then there was a blast…everyone was thrown.”

Okada was inside her house when the blast hit but the force was so strong it hurled her out of the house and onto the ground where she was knocked unconscious. She woke up throwing up a strange dark color.

After detonation, the nuclear bomb named, “Little Boy,” gave off an extreme sweltering heat of 4,000 degrees Celsius (about 7,300 degrees Fahrenheit).

“I remember my mother drenched in blood with shards of glass in her body from the windows and naked people everywhere because all their clothes had burned off.”

“They were crying and groaning for help. ‘Water! Help me!’”

Hushed scattered gasps were heard as Okada shared a disturbing memory a child’s melted eyes melted that popped out of its head and hung from the sockets.

“Three days Hiroshima burned. It was breakfast time so many homes had their heat gas and coal burners on which spread the fire from bomb…it was like the flames were coming after us,” Okada said gazing into the crowd.

The people of Hiroshima who had not died instantly and could move were focused on one thing and one thing only…escaping.

“I remember a little girl tugged on my work pants and tried to ask for help, but I pulled away to save myself,” said Okada looking at the ground, “As I departed, I heard her yell ‘Mommy!’ as flames engulfed her, and I just ran away.”

According to Okada, nothing was left of the city of Hiroshima except rubble, nothing stood anymore, and she could see all the way to the coastline and off into the sea from where she was in North Hiroshima.

“Every day my mother went looking for my 12-year-old sister who left that morning and never came back,” Okada said with a cracking voice full of emotion.

“There were shelters that many kids were taken to and my mother checked all of them for her…we couldn’t even find her bones. All we could do was have an empty grave and marker with her name.”

The following days after the bombing the survivors of Hiroshima grieved and tried to do the best they could to survive.

About 6,000 children were orphaned and lived on the streets just like eight- year old Emiko Okada and the remaining members of her family.

On the streets the Okada family witnessed children fight and steal food to eat and get used by gang members who took over the war-stricken city.

After the bombing, Okada was so weak that she did not have the strength to get up and spent a lot of her time laying down.

“It took 12 years to understand radiation disease and figure out what was wrong with me. We discovered that I had aplastic anemia (a disease that develops when your body stops producing new blood cells).”

“The atomic bomb isn’t something to talk about in terms of ‘how many people died and were injured’—that is not the meaning,” Okada said as she began to close the presentation.

“As long as there are nuclear weapons there is no peace.”

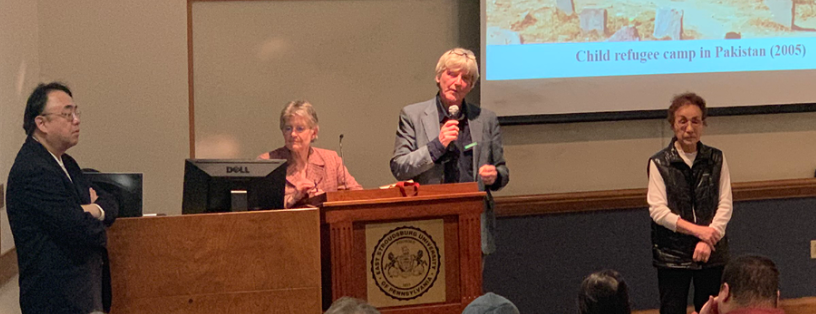

Emiko Okada was accompanied by Steven Leeper, who has played a large role in the nuclear disarmament movement and was the chairman of Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation in 2007 until 2013.

Leeper and Okada have been to United Nations assembly meetings to speak on the destruction that nuclear weapons cause.

Their petition, “Hibakusha Appeal” is to get one billion signatures to present to the U.N. so the devastations that the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings caused does not happen again.

Join the fight to end nuclear weapon production and countries using them against each other by going to https://www.peacinstitute.org/endnukesnow and sign the petition now.

Email Jazmin at:

jcole17@live.esu.edu